Nearly 3 in 5 young people in the LGBTQ+ community have experienced hate speech online

The young people facing most risks online, may also rely most on online support

The Internet is an important way in which young people connect with their friends. One of the most common things young people do (55%) is to message friends and family, play online games (49%), and browse posts, videos and images from others (48%).

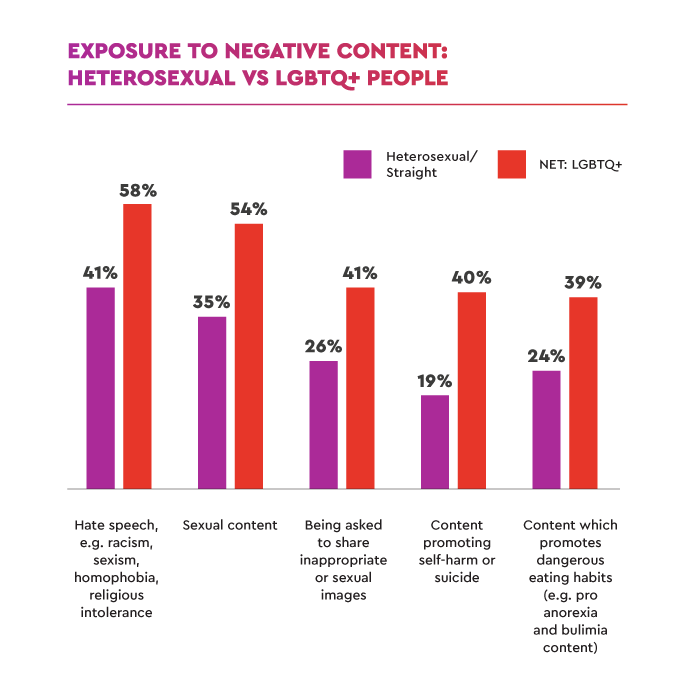

Minority ethnic and young LGBTQ+ people are more likely to experience upsetting events online. Nearly 3 in 5 (58%) young LGBTQ+ people, and over 2 in 5 (43%) of young people who are Black, Asian or another ethnic minority, have experienced hate speech online, compared to 37% of young people overall. This equates to 870,000 young LGBTQ+ people, 1.4 million young Black, Asian or other ethnic minority people, and 4.1 million young people overall.

Other research shows LGBTQ+ individuals are more likely to have lower levels of wellbeing compared to their heterosexual peers and are more likely to find solace in online communities.

However, LGBTQ+ young people are more likely to experience hate speech online (58% vs 41% of heterosexual people), see content promoting self-harm or suicide (39% vs 24%), be asked to share inappropriate or sexual images (41% vs 26%), and see content which promotes dangerous eating habits (39% vs 24%).

Our research shows that young people who are Black, Asian, or from other ethnic minority groups, are more likely to experience hate speech than those of white ethnicity (43% vs 37%).

Why does this matter?

We know how important forming relationships and staying connected online is for young people. This is particularly important for young people who are minority ethnic or LGBTQ+ who face more challenging circumstances growing up. These same people are also more likely than average to experience upsetting content online. This can further marginalise these young people from experiencing the benefits of going online for support, interaction and boosting wellbeing. Positive and negative experiences are interwoven – and both these factors are heightened for minority groups.

Implications

- How will strategies to protect people in certain groups differ when they are being individually sought out and discriminated against online vs encountering content that discriminates against them?

- What are the different responses needed towards protecting groups from abuse and enabling the freedom to enjoy the benefits of the internet without fear?

- Is exclusion from online spaces due to toxicity feeding a cycle of marginalisation?

- What impact is this having on the digital resilience of more vulnerable groups?